2023 saw the famous Michelin Guide awarding stars in Vietnam for the first time, with selections in both Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.

This arrival is positive for the local dining scene but also triggered many reactions when the winners were announced.

In this article, you’ll find the full list of winners in each category (with links to our reviews of these establishments when available). I’ll also provide my personal in-depth opinion on this issue as a Frenchman living in Vietnam for over 15 years.

If you are not familiar with how the Michelin Guide works and what a Star can represent for a restaurant we recommend reading this article first: Everything you should know about the Guide Michelin

Michelin Guide Hanoi & Ho Chi Minh City 2023 Winners

Stars

Amongst the 103 restaurants included in the Guide in 2023, one Michelin Star was awarded to 3

restaurants in Hanoi, and 1 restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City.

- Anăn Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City)

- Gia (Hanoi)

- Hibana by Koki (Hanoi)

- Tầm Vị (Hanoi)

No restaurant were given Two or Three Stars.

Bib Gourmand

This award recognizes friendly establishments that serve good food at moderate prices.

Bib Gourmand full list (13 restaurants in Hanoi 16 in HCMC)

Hanoi – Bib Gourmand Establishments

- 1946 Cua Bac – Vietnamese

- Bun Cha Ta (Nguyen Huu Huan Street) – Noodles

- Chả Cá Thăng Long – Vietnamese

- Chào Bạn – Vietnamese

- Don Duck Old Quarter – Vietnamese

- Habakuk – European Contemporary

- Phở 10 Lý Quốc Sư – Noodles

- Phở Bò Ấu Triệu – Street Food

- Phở Gà Nguyệt – Street Food

- Phở Gia Truyền – Street food

- The East – Vietnamese

- Tuyết Bún Chả 34 – Street Food

- Xới Cơm – Vietnamese

Ho Chi Minh City – Bib Gourmand Establishments

- Bếp Mẹ ỉn (Le Thanh Ton) – Vietnamese

- Chay Garden – Vegetarian

- Cơm Tấm Ba Ghiền – Street Food

- Cuc Gach Quan – Vietnamese

- Dim Tu Tac (Dong Du) – Cantonese

- Hồng Phát (District 3) – Noodles

- Hum Garden – Vegetarian

- Phở Chào – Noodles

- Phở Hoà Pasteur – Noodles

- Phở Hoàng – Noodles

- Phở Hương Bình – Noodles

- Phở Lệ (District 5) – Noodles

- Phở Miến Gà Kỳ Đồng – Street Food

- Phở Minh – Noodles

- Phở Phượng – Street Food

- Xôi Bát – Vietnamese

An additional 70 other restaurants also joined the Michelin Guide without beings awarded (known as the Michelin Selected restaurants).

Michelin selected full list (32 restaurants in Hanoi – 16 in HCMC)

Hanoi – Michelin Selected Restaurants

- A Bản Mountain Dew – Vietnamese

- Akira Back – Japanese

- Azabu – Japanese

- Backstage – Vietnamese Contemporary

- Bánh Cuốn Bà Xuân – Street Food

- Bếp Prime – Vietnamese

- Bún Chả Đắc Kim – Street Food

- Bún Chả Hương Liên – Street Food

- Cau Go – Vietnamese

- Chả Cá Anh Vũ – Vietnamese

- Chapter – Vietnamese Contemporary

- Cồ Đàm – Vegetarian

- Duong’s – Vietnamese

- El Gaucho – Steakhouse

- Etēsia – European Contemporary

- French Grill – French Contemporary

- Hemispheres Steak and Seafood Grill – Steakhouse

- Highway4 (Hang Tre Street) – Vietnamese

- Izakaya by Koki – Japanese

- Khói – Barbecue

- La Badiane – Fusion

- Labri – European Contemporary

- Le Goût de Gia – European Contemporary

- Ngon Garden – Vietnamese

- Ốc Di Tú – Seafood

- Ốc Vi Saigon – Seafood

- Phở Gà Cham (Yen Ninh Street) – Noodles

- Phở Tiến – Noodles

- Quán Ăn Ngon – Vietnamese

- Senté (Nguyen Quang Bich Street) – Vietnamese

- T.U.N.G. dining – European Contemporary

- Tanh Tách – Seafood

Ho Chi Minh City – Michelin Selected Restaurants

- 3G Trois Gourmands – French

- Å by T.U.N.G – European Contemporary

- An’s Saigon – Innovative

- Bà Cô Lốc Cốc – Seafood

- Bếp Nhà Xứ Quảng – Vietnamese

- Bờm – Vietnamese Contemporary

- Bún Thịt Nướng Hoàng Văn – Street Food

- Cô Liêng – Street Food

- Coco Dining – Innovative

- Da Vittorio – Italian

- Đông Phở – Vietnamese

- Elgin – European

- Esta – Asian Contemporary

- Fashionista Café – European Contemporary

- Hervé Dining Room – French Contemporary

- Hoa Tuc – Vietnamese

- La Villa – French

- Lai – Cantonese

- Lửa – Japanese

- Madame Lam – Vietnamese

- Nén Light – Contemporary

- Nous – Innovative

- Ốc Đào – Seafood

- Octo – Spanish

- Okra FoodBar – European

- Olivia – European Contemporary

- Phở Hùng – Noodles

- Phở Việt Nam (District 1) – Noodles

- Quince Eatery – Mediterranean Cuisine

- Rice Field – Vietnamese

- Sol Kitchen & Bar – Latin American

- Square One – International

- Stoker (District 1) – Steakhouse

- The Monkey Gallery Dining – European Contemporary

- The Royal Pavilion – Cantonese

- Tre Dining – Vietnamese Contemporary

- Truffle – French Contemporary

- Vietnam House – Vietnamese

Opinion

As a Frenchman with a strong interest in the Vietnamese food scene for many years, I was eagerly anticipating the arrival of the Michelin Guide in Vietnam.

I knew that the awards had a high chance of triggering reactions (as all prestigious rankings do), but I was not prepared for the overwhelmingly negative reception, especially among the locals.

Here are a few thoughts on the matter:

Congratulations to the awarded chefs (sincerely)

First and foremost, it needs to be said: Congratulations to the chefs!

Despite the plethora of negative comments, we shouldn’t overlook the fact that everyone in the restaurant industry works hard. In a world where quick money schemes are promoted everywhere, it’s refreshing to shine a spotlight on people dedicated to their craft. While there may be criticisms of the restaurant industry, I genuinely believe that nobody enters it to make a quick buck. It’s a given that everyone who received an award had put in tremendous effort to get there.

In retrospect, seeing all the nominees happy after the announcement was truly heartwarming.

This is great for Vietnam’s food scene in general

I also believe that the presence of the Michelin Guide is a net positive for the country as a whole:

Tourists generally praise Vietnamese food but usually stick to a few iconic street food dishes during their stay, such as Pho, Bun Cha, and Banh Mi. When the Michelin Guide arrives in a country, it signals to tourists that they can expect a wide variety of culinary experiences, even at the high end. In other words, the Guide is an excellent way to encourage tourists to spend more on quality food experiences.

Thailand understood this well, as the Tourism Authority of Thailand sponsored the arrival of the guide in 2017, expecting a 10% boost in tourist spending per head in Thailand as a result.

I also have the impression that local Vietnamese are still hesitant to pay a premium for elevated Vietnamese food, while they are less cautious about spending money when visiting a steakhouse. However, the combination of great ingredients, creativity, service, and presentation needed to bring Vietnamese cuisine to the fine dining category can only be achieved if local customers are willing to pay more for this elevated experience. The Michelin Guide could help change this dynamic, and that’s not a minor detail: locals are the foundation of a food scene, not tourists.

We can be hopeful that other Vietnamese restaurant owners, after witnessing the success of establishments like Gia and Anan Saigon in obtaining their first Michelin star (and the subsequent increase in business), will be encouraged to push their limits and elevate Vietnamese cuisine to the fine dining realm, even if it means charging their customers a bit more.

Corruption allegations?

I’d like to address the corruption accusations that I’ve seen mentioned several times on social media. Yes, Sun Group sponsored the arrival of the guide in Vietnam, and there is a clear conflict of interest as they own restaurants. However, beyond these facts, there is little that can be said without entering into the realm of speculation. These are serious accusations. If buying awards were that easy or common, the Michelin Guide and its stars would have no value. We are talking about a hundred-year-old institution here.

If you have proof of corruption, you can directly contact reputable news outlets like The New York Times or Le Monde, who would eagerly cover such a significant scandal. We, too, would be interested in reporting on it 🙂

Give it a few years

One more word to the people who hated these awards: Give the guide a few years before forming your final opinion. It takes time to build a comprehensive guide that makes sense.

The scope of what they’re aiming to cover is also way larger than The World’s 50 Best Restaurants, which strictly focuses on fine dining. Inspectors of the guide are also “new” to the local scene, and obtaining a decent guide is an incremental process. The last edition of the Thailand Michelin Guide awarded 29 one stars and 6 two stars… For its first edition in the country in 2007, only 17 restaurants received Michelin Stars.

Does it mean that everything is perfect? Clearly no. I, like many others, have personally been disappointed by some choices.

What about the diversity of Vietnamese food?

I am specifically talking about the 29 restaurants selected in the “Bib Gourmand” category, where 12 of them are Pho (4 in Hanoi and 8 in Ho Chi Minh City).

I have always believed that what made Vietnamese food so interesting was its incredible diversity. The diversity of its climate and the contrast between sea and mountain are the roots of a wide range of dishes. I haven’t even mentioned what ethnic minorities are also adding to the Vietnamese food landscape.

The Bib Gourmand selection is supposed to signal great food at a moderate price, and there are so many places in both Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City that could have fit into this category. When there are so many possibilities, I would have expected the guide to try to use this category to “tell a story” about the current Vietnamese food scene.

The diversity of affordable street food available in Vietnam would have been an obvious choice.

With these 12 Pho selections and a few other questionable picks, I cannot help but feel that the Bib Gourmand failed to offer a compelling narrative with this category.

Which resources have been allocated to build this guide? Was it enough?

This is the main question. Analysts estimate that Vietnam has over half a million restaurants in the country. While I don’t have the exact data for Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, we can easily agree that the Food scene in both cities is massive. Building a Michelin guide for these cities would require visiting thousands of establishments, especially for a first edition where the authors cannot rely on experiences collected in previous years.

The composition of the Michelin guide team in Vietnam then makes a significant difference.

Were they composed of 2-3 people or a dozen?

This information is crucial to understand the extent of their coverage. It’s legitimate to ask these questions, especially when we see that the guide awarded one of its four stars to a Japanese restaurant (Hibana), but no Japanese restaurant made the cut for the Bib Gourmand.

According to the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), there are currently over 2,500 Japanese restaurants in Vietnam, with many of them located in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. How many of these establishments have been visited by inspectors?

The same question applies to the decision to award a Bib Gourmand to a Dim Tu Tac branch. How many points of comparison did they have before making this decision? Did they spend enough time in Cho Lon before singling out this specific restaurant as a good value for Chinese food?

These are not rhetorical questions. In 2004, Pascal Remy, a Michelin inspector for 16 years, created a scandal by revealing that the Guide was employing only five people in France to review over 10,000 restaurants. It was also disclosed that some places awarded stars had not been visited every year. Although this was nearly 10 years ago, the number of inspectors is still a well-kept secret by the Guide.

Where are French chefs?

The Michelin Guide has historically been criticized for being elitist and “too French.” This could explain why the guide has been reluctant to award stars to the great fine dining French tables in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.

International inspectors likely have many point comparisons when reviewing a restaurant of this type, and French gastronomy was likely not their focus when approaching Vietnam for the first time.

But hear me out: French fine dining establishments in Vietnam are an important part of the culinary landscape. When Vietnam opened its economy in 1986 with Đổi Mới, the French were among the first Europeans to significantly come back to the country and try to do business, including in the hospitality industry.

Long-standing places like La Badiane, La Villa, Le Corto, Les Trois Gourmands, to name a few, have trained countless locals in the requirements of fine dining cuisine in their restaurants.

I’m not qualified to know exactly what they “missed” to reach the “star territory,” but I’m sure that if any of these great French tables had been awarded, it would not have felt out of place.

But what exactly is the Michelin guide trying to do?

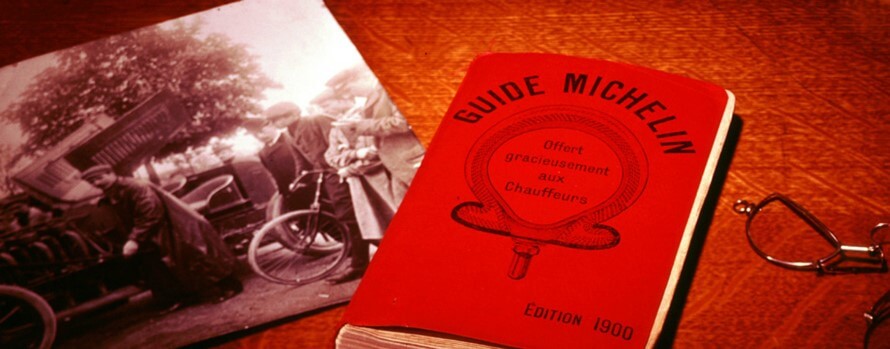

This reflection may seem a bit trivial, but let’s consider its evolution.

When the Michelin guide was created in 1900, it primarily served as a marketing tool for its parent company. By recommending great restaurants, the guide aimed to encourage people to drive longer distances, thus needing to buy new Michelin tires. In those days, the guide also listed the best places for car repairs alongside the best dining establishments. It was essentially a handy handbook that everyone could have in their car, reminding them to buy Michelin tires when necessary.

Over time, the guide’s purpose changed as the star ranking system (1 to 3 stars) became the most important classification for fine dining in France and Europe.

In the 21st century, the Michelin Guide has undergone significant transformations that reflect profound changes:

The guide is no longer exclusively focused on France or Europe. It has expanded rapidly, starting to cover the USA in 2006, Japan in 2007, Hong Kong and Macau in 2009, and many other countries since then, including Vietnam.

To address accusations of snobbishness and excessive favoritism toward French cuisine, the guide began awarding stars to restaurants that did not strictly fall into the fine dining category.

Notable examples include Singapore and Thailand, where Michelin stars were awarded to Street Food vendors, shedding light on their significant culinary cultures that were potentially at risk due to rapid modernization.

I have the feeling that the decision to award a star to Tam Vi in Hanoi in the first edition of the Vietnamese guide followed a similar thought process.

Tam Vi offers good, affordable traditional Hanoian home cooking. The dishes are delicious and represent good value, but there is no intention to innovate or provide a completely unique culinary experience.

When the Michelin Guide awards stars to restaurants focusing on traditional home cooking or iconic street food, it blurs the lines of the criteria for receiving stars. The guide officially states that decoration, service, or formal elements are not taken into account; only the food matters.

However, if a restaurant doesn’t even need to offer truly unique, personal, or innovative food to receive a star, it disrupts the Michelin ranking system.

The Michelin Guide is, in essence, a ranking system. Two-star restaurants are expected to offer a more unique experience than one-star restaurants, which are better than those without stars.

It becomes an interesting discussion among food enthusiasts to contemplate whether the personal take on Vietnamese food at Gia and Anan is worthy of the stars they received (or more/less).

There are points of comparison that can be made even when considering European restaurants that have also been awarded stars. Introducing restaurants with a completely different ambition into this discussion explains part of the criticism we hear.

Similar criticisms can be applied to the Bib Gourmand category. Initially, before 1997, the guide simply flagged restaurants with a red “R” symbol to indicate that they offered good cuisine at reasonable prices. It was merely a mention added to the name of the restaurants in the guide, not an award.

Fast forward to the present, Bib Gourmand has become a sought-after award in a category that could include 90% of the restaurants in the country, while inspectors only have the chance to visit a few of them. It inherently creates frustration and disappointment.

One possible solution to address the overwhelming size of the category that seems too large to make sense would be to utilize the awards as a means to tell a compelling story or shed light on a particular aspect of Vietnam’s food scene that would benefit from recognition.

However, in my opinion, the 2023 Bib Gourmand and its selection of 12 Pho restaurants did not achieve this.

This is even more disappointing when we know that the Guide introduced the Green Star award in 2020 to recognize restaurants leading in sustainable practices.

Given the challenges Vietnam is currently facing, it would have been highly valued to see environmentally-conscious restaurant owners receive the recognition they deserve. Unfortunately, no Green Stars were awarded in this first edition, representing a missed opportunity. Regrettably, the guide fell short in this regard.

Ultimately, I remain convinced that the arrival of the Michelin Guide has had a positive impact on the Vietnamese food scene, despite its flaws. I’m genuinely interested to see how its selection will evolve in the upcoming years.