As a beer enthusiast who’s visited Munich’s famous Oktoberfest in the past, I recently had the chance to return to Bavaria and spend several days immersed in one of the richest and oldest beer cultures in the world.

While we’ll have separate articles dedicated to Oktoberfest itself and the great city of Munich, my focus here is to illuminate the incredible diversity of beers crafted in this region of Germany.

This guide stems from my personal experience. Bavaria’s beers marked the beginning of my own “beer journey” over 20 years ago. Returning to sample these traditional beers once again was truly special.

In the following sections, we’ll be providing an overview of the main beer styles brewed in Bavaria, from crisp lagers to malty Bocks and smoky Rauchbiers.

The goal is to highlight the incredible diversity and craft behind some of the world’s oldest beers.

1. Helles

Characteristics and Profile

Helles is currently one of the most popular, if not the most popular, beer styles in Bavaria. As a lager, Helles is the Bavarian interpretation of the larger pilsner family.

The name translates to “pale or bright” referring to its golden, clear appearance from filtering.

Compared to Czech pilsners, Helles has a distinctive flavor profile – less crisp, leaning towards more sweet, malty notes with sometimes hints of spices while maintaining very low bitterness.

This makes Helles highly refreshing and drinkable, even in large quantities, especially during the hot summer months in Bavaria. A perfect beer for shouting “Ein Mass bitte schöne!”

Bit of History

Believe it or not, Helles has not always dominated in Munich. Far from it – it’s quite a story.

The lager style was initially developed in Plzeň, Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). This crisp, light beer quickly gained popularity across Europe. However, Bavarian brewers first scorned lagers as inferior to the dark, full-bodied beers they had been perfecting for centuries.

But lager was more than just a fad. Eventually, brewers in Munich developed their version – Helles – which rapidly overtook the older traditional styles in popularity.

Helles Beers

There are 6 main historical brewers in Munich, each producing their Helles. It’s nearly impossible to spend time in Munich without sampling these ubiquitous beers, offered in beer gardens, bars, and restaurants everywhere.

The Big Six:

- Löwenbräu

- Spaten

- Hofbräu

- Augustiner

- Hacker-Pschorr

- Paulaner

While personal preference varies, Augustiner’s Helles is a fine example. But Munich’s major brands are only part of the Bavarian beer experience.

Bayerische Staatsbrauerei Weihenstephan

Excellent Helles are also brewed outside Munich. For example, Weihenstephan, located in Freising, produces some of the world’s most renowned Helles. Brewing since 1040 AD, Weihenstephan claims the title of the world’s oldest brewery.

Several of their beers stand out, including the award-winning Weihenstephaner Original Helles.

2. Pils & Dortmunder

These beers do not originate from Bavaria, but due to their popularity, the major Munich breweries began producing them as well.

Pils

We previously mentioned the difference in taste profile between Helles and Pils. You will be surprised to know that some of the most traditional breweries in Munich also added to their offering “Pils” beers that will be as close as you can imagine to the Czech beers.

We tried the Augustiner Pils in a local restaurant and it was everything and more than what I could expect from a good Pils.

Dortmunder Export Lager or Export Helles

These beers are originally from the city of Dortmund in the North Rhine-Westphalia region but some Bavarian breweries like Augustiner with their Edelstoff are also brewing their own “Export” beers.

These beers will keep the malt-forward flavor and “sweetness” of a Helles but will add the bitterness you’ll usually find in Pils beers. These beers are also usually slightly stronger (6 degrees).

3. Weissbier – Hefeweizen

Personally, this is the category where Bavarian’s beers truly shine. We cannot recommend enough to try them at least once in your life.

Characteristics and profile

They have very distinctive characteristics that make it impossible to confuse them with other types of beers:

- Most beers you are familiar with are brewed with malted barley but in Weissbiers 50% or more wheat malt is used.

- Hefe” means “with yeast,” hence the beer’s unfiltered and cloudy appearance. The particular ale yeast used produces unique esters and phenols of banana and cloves with an often dry and tart edge, and some spiciness. The “unfiltered” character of the Weissbier is often underlined by the appellation “naturtrüb” as opposition for “Kristall” for filtered Weissbier (more below).

- You will find in Hefeweizen little to no hop bitterness, and a moderate level of alcohol.

- Weissebier are also not technically white – their robe will be more pale yellow to gold.

If you are used to bitter beers like IPA or dry and light beers (like Lager) give it a try to Weissbier it’s going to be a truly different experience.

Munich Weissbier

Being one of the most traditional types of beer brewed in Bavaria – most of the brewers will have their own Weissbier.

- Among them the Historical brewer of Munich – I would absolutely recommend the Franziskaner Weissbier brewed by Spaten-Franziskaner-Bräu as the first choice.

- The Hefe-Weissbier from Paulaner is also an excellent choice. It encapsulates everything you may expect from a great Weissbier while remaining easy to approach.

Outside of Munich ( but in Bavaria)

The big brewers of Munich do not have a monopoly on good Bavarian Weissbier. I would even say that the very best ones are to be found outside:

– Andechs: This beer is my personal favorite Hefeweizen to the point that we went to visit the monastery where the beer is brewed ( an hour’s train ride from Munich).

The beer is cloudy/hazy with a dark gold robe and with incredibly smooth and complex taste. You’ll find all the traditional flavor profiles of a Hefeweizen ( Clove / Citrus / Bananas) but well balanced with a hint of bitterness that perfectly balances the sweetness of the beer.

– Weihenstephaner Hefeweissbier: This beer is considered by many beer aficionados as one of the best or if not the best Hefeweissbier in the World. It’s produced by Weihenstephaner in Freising who claim the title of the oldest brewery in the world (already mentioned previously for its Helles).

– Schneider Weisse: No discussion on Weissbier is complete without mentioning Schneider Weisse. This historic brewery, located in Kelheim, has specialized in brewing wheat beers for hundreds of years.

Schneider Weisse produces a good traditional Hefeweizen, but the brewery is particularly renowned for its strong Weissbiers, which we’ll explore in more detail later…

– Erdinger: One last beer worth mentioning: the Erdinger Hefeweizen. This beer is produced in the town of Erding and has everything needed to be a good Weissbier in addition to the advantage of being frequently available outside of Germany.

So if you see it on the menu during your travel and feel like a Weissbier – do not hesitate to order it.

Weissbier variations

Kirstall Weissbier: This beer is a Hefeweizen that is filtered to remove the yeast and wheat proteins that contribute to its cloudy appearance. This will make beer “lighter” but also tone down some of the most interesting flavors usually found in a Hefeweizen.

Most Weissbiers are also often brewed in Dunkel (dark) and Bock (strong) versions. All the details in the two sections below:

4. Dunkel

Dunkel means “Dark” and is the original style of beer produced in Bavaria before the Pils / Helles “revolution”.

We can divide them into two main categories with distinct profiles:

Munich Dunkel

Even if Helles are now popular, Dunkels remain a cornerstone of Bavarian Beer Culture:

- The beer is defined by its dark brown or coppery (reddish when held up to the light) color that comes from the use of Munich (or sometimes Vienna) malts.

- Munich Dunkels are not stouts! They have a light body and moderate alcohol content around 4-5% ABV.

- They are mildly hopped with some bitterness, allowing the Munich malt character to take center stage.

- Dunkels have a smooth, rich malty flavor with notes of bread, toast, nuts, and chocolate.

All of this makes “Munich Dunkel” a type of beer very refreshing and approachable.

I particularly recommend it for people associating “Dark / Black” beers with full body / high alcohol styles – with a Munich Dunkel they are going to discover something completely new.

Recommended: Almost all the breweries mentioned previously have their own Dunkel beers which means you should not struggle to find them.

We personally tried the Augustiner Dunkel – which was refreshing while offering at the same time a rich malty flavor.

It was a very pleasant beer but honestly, I do not have enough points of comparison to recommend it over other Munich Dunkels.

Dunkel Hefeweizen

Like other Weissbiers, a Dunkel Hefeweizen is made of at least 50% Wheat malt. What makes it different from “regular Weissbier” is the addition of darker Munich Malt (or Vienna Malt). These darker malts add sweetness and caramel, toffee, vanilla, or nutty flavors.

Regarding the flavor profile, it’s not a stretch to think of Dunkelweizen as a cross between a Hefeweizen and a Munich Dunkel. The style displays characteristics of both.

These beers are clearly a true part of the Munich beer identity – I would just not recommend them if you are looking for light, crisp, and refreshing beers.

Recommended Dunkel Hefeweizen:

Both Spaten-Franziskaner-Bräu and Weihenstephaner have renowned Dunkel Hefeweizens.

Considering the quality of their Weissbiers I think I won’t take a big risk recommending them.

Also tested recently was the Hofbräu Schwarze Weisse which can be found in Vietnam. It’s clearly an easy way to discover this style but overall slightly lacked complexity for my personal taste.

What about Schwarzbier?

Schwarzbier is a notch darker than Dunkel —it’s the darkest of all the German lagers (the name translates to “black beer”). Despite its appearance, Schwarzbier remains an easy drinker—it’s only about 5% ABV and is lighter in body.

It’s not a traditional Bavarian style so we’ll save a more detailed profile for another time.

5. Bock

Do you think that you won’t find strong, high-alcohol beers in Bavaria?

No, you’re wrong – Let’s talk about Bock.

The style now known as Bock was first brewed in the 14th century in Lower Saxony but later adopted in Bavaria by Munich breweries in the 17th century. Bocks were traditionally associated with special occasions, mostly religious festivals such as Christmas or Easter.

There are several kinds of Bocks, each with their own characteristics but commonly having a higher alcohol content.

Traditional Bock

Traditional Bock is a strong lager of around 6-7% alcohol by volume (ABV). It has a clear, copper-to-brown color with a creamy white head.

The flavor is malty and toasty, sometimes with caramel notes. The low hop bitterness provides just enough balance to the natural sweetness.

Maibock

Also called Heller Bock, Maibock is a pale, strong spring lager with around 6-8% ABV. The flavor is drier and more hoppy than a traditional Bock which provides more bitterness, but the overall focus remains the malty richness.

Hofbräu has a long tradition of brewing this style, claiming to be the very first to brew Maibock in 1614. We unfortunately did not have the chance to taste it.

Doppelbock

Doppelbock is an even stronger, malt-focused lager originally brewed by monks in Munich. It ranges from 7-12% ABV with a dark gold to brown color.

The flavor is very rich and malty with a noticeable but smooth alcohol presence.

Paulaner’s Salvator is a classic example of the style. Monks started brewing this Doppelbock over 375 years ago, and it is said to be the origin of why many Doppelbocks have names ending in “-ator.”

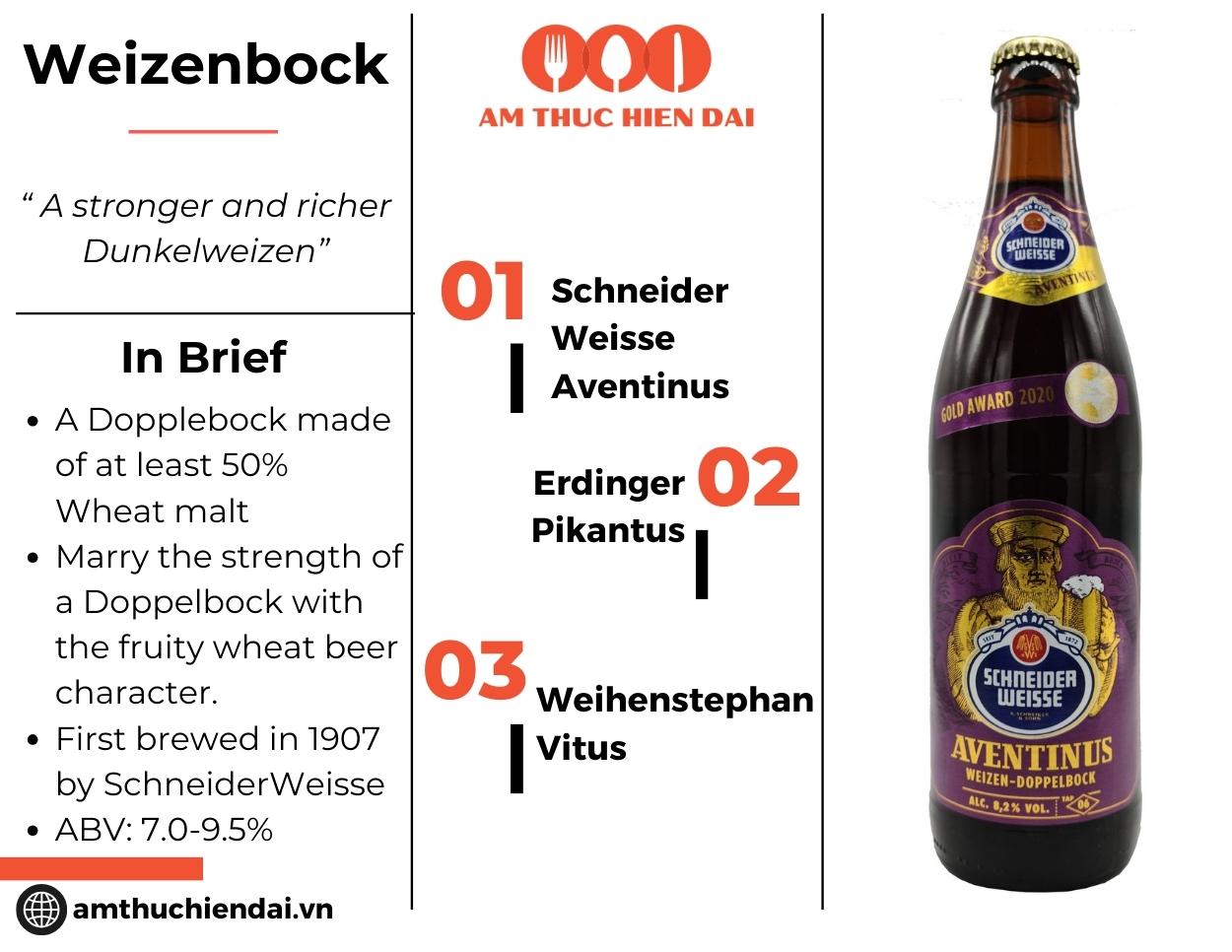

Weizenbock

Like a Dunkel Weissbier, Weizenbock combines darker Munich malts and wheat beer yeast but with a higher alcohol content.

In terms of taste, a Weizenbock marries the strength of a Doppelbock with the fruity wheat beer character.

This style was first brewed in 1907 by Schneider Weisse under the name Aventinus. Their Aventinus Tap 6 is still considered the standard for Weizenbocks today.

Great alternatives are Weihenstephaner Vitus and Erdinger Weissbier Pikantus.

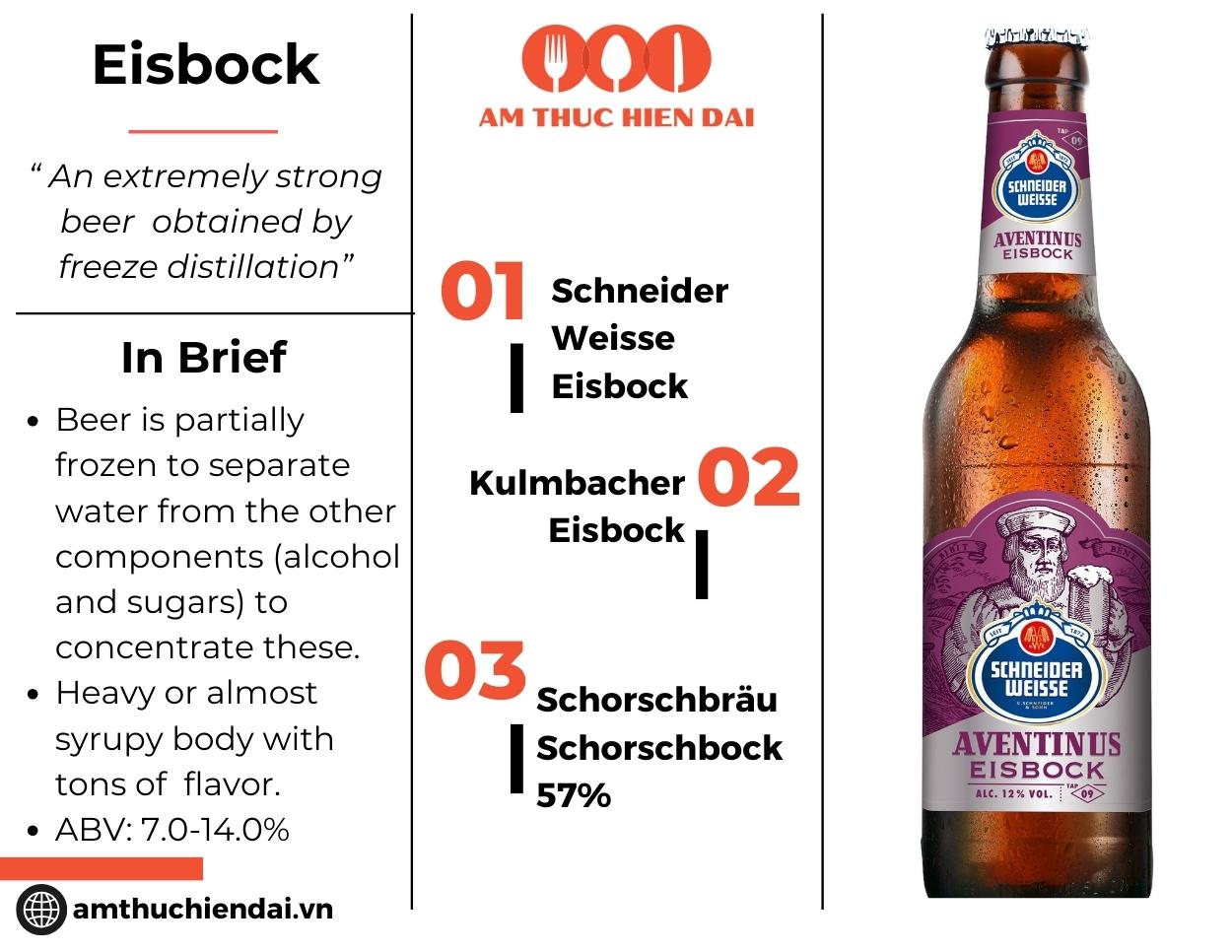

Eisbock

Why are beers not brewed with higher alcohol levels? Too much alcohol during fermentation kills the yeast, stopping fermentation and alcohol production.

Eisbock creatively solves this by partially freezing a Doppelbock and then removing the frozen water to concentrate the flavor and alcohol, reaching 8-14% ABV. This results in intense malty flavors balanced by significant alcohol presence and fruity or chocolate notes.

Probably not for lovers of light, refreshing beers!

One of the most renowned is the Aventinus Eisbock, a stronger version of Schneider’s Weizen Doppelbock. Legend says this style was invented by accident when extra Aventinus froze during cold winter transport in the 1930s.

The World’s Strongest Beer?

Using the Eisbock ice concentration technique, the Bavarian brewer Schorschbräu attempted to create the world’s strongest beer – the Schorschbräu Schorschbock 57%. As the name suggests, this experimental brew reached a staggering 57% alcohol by volume.

However, this ultra-high alcohol beer is very hard to find and considered by most beer purists as more of a gimmicky record chase than a serious brew.

6. Rauchbier “Smoked Beers”

Rauchbier is another truly special Bavarian beer style.

Rauchbiers are made with malt dried over an open beechwood fire, which imparts a pronounced smoky flavor.

When we talk about smoky flavor in these beers, it’s not just “notes or hints of smoke” – the smokiness shapes the entire taste profile and can be quite overpowering. As you can imagine, it’s a taste that’s not for everyone and an acquired liking for most.

A Bamberg tradition

Rauchbiers are a very local tradition specific to the Northern Bavaria town of Bamberg.

The main brewery specializing in Rauchbiers is Schlenkerla (Heller-Bräu Trum GmbH). Their website provides an in-depth explanation of the technical process behind Rauchbier if you want to learn more.

Rauchbier is just a specific way of drying the malt used in the beer – you can then use it to brew different traditional styles.

For example, Schlenkerla offers Rauchbier versions of:

- Märzen

- Bock

- Doppelbock

- Weizen

- Helles

I had the chance to try a Schlenkerla Rauchbier over 15 years ago and still vividly remember its intense initial smoky taste that gradually gave way to the underlying beer’s flavor profile. An experience every beer lover should try at least once!

7. Märzen – Oktoberfest Beer

You will likely think about the Oktoberfest when first hearing about this style of beer. It makes perfect sense considering the popularity of the festival.

In this section, we’ll focus just on the beer itself rather than the festival – we’ll cover Oktoberfest history and traditions in a dedicated article.

The name “Märzen” refers to the fact that it was traditionally brewed in March and layered over the summer months before being tapped for fall consumption. This included the Oktoberfest celebrations.

Characteristics and Profile

- Märzen is made with Munich malt (sometimes blended with Vienna malt).

- This imparts a deep amber or copper color and pronounced malty sweetness.

- A moderate hop bitterness helps balance the rich malt character.

- The beer is medium to full-bodied with flavors of bread, biscuits, toasted nuts, and/or caramel.

- Alcohol content ranges from 5-6% ABV.

So is this the beer everybody drinks at Oktoberfest today?

Well, no – people are actually drinking Festbier, a different German lager style that replaced Märzen at the festival in the late 20th century.

Developed and pioneered by Paulaner, golden-hued Festbier is easy to drink with lower alcohol content.

The brewery first debuted it at Oktoberfest in the early 1970s. Its popularity with attendees grew, and by the 1990s all the beer served was Festbier, with Märzen completely phased out.

8. Radler

Well, a lot of people (maybe including myself) will argue that Radlers are not “real beers.” But they are so popular in Bavaria (and Germany in general) and such a true part of local Bavarian culture that we have to mention them here.

Radler commonly consists of a 50:50 mixture of beer and a lemon-flavored soda (like Sprite for example).

This naturally leads to very low-alcohol beers around 2-3% ABV. But the resulting blend is sweet and refreshing, making Radlers a popular summer drink.

All the major breweries in Munich produce a “Radler” version of their beers, and you’ll always see them on the menu at any bar, beergarten, or restaurant in Bavaria.

Bit of History

The term Radler originates from a drink called Radlermass (“cyclist liter”) popularized by innkeeper Franz Kugler in the small town of Deisenhofen just outside Munich. During the cycling boom of the roaring 1920s, Kugler created a bike trail from Munich through the woods leading right to his inn where he started to serve Radlers.

This allowed Kugler to popularize the beer and lemonade blend, and the Radler name stuck, even if technically he didn’t invent the blend himself.

9. Craft Beers in Bavaria

You would think that a region with such deeply ingrained brewing traditions and avid beer consumption would be a craft beer paradise.

Well, not exactly – one could argue it’s the opposite. In Germany, small craft breweries have only a tiny 0.5% market share (compared to 15-20% in the US and 5-8% in the UK).

Munich’s taps are dominated by the traditional beers of the “Big Six” megabrands: Augustiner, Hacker-Pschorr, Hofbräu, Löwenbräu, Paulaner, and Spaten.

These companies have prospered for centuries thanks to favorable regulations helping cement their power, going back as far as the 1516 Beer Purity Law.

Oktoberfest statutes allow only beer brewed with Munich’s water to be served, and the Big Six control the wells and reservoirs providing it. Munich’s mega-breweries also now own many beer hall locations in prime areas like the massive city parks.

Add to this the fact that most Bavarians are accustomed to drinking these same familiar brands for decades, as well as the breweries’ enormous marketing budget (Paulaner sponsors Bayern Munich). Suffice it to say, that small independent craft breweries face stiff headwinds.

But there is a new generation of passionate young brewers interested in both bringing American-style craft beers like IPAs to Bavaria, as well as putting their spin on time-honored Bavarian styles.

During our visit, we admittedly did not take the time to try these craft beers, focused as we were on discovering the full range of traditional Bavarian brews. But it will be exciting to see how the craft beer scene evolves in this legendary beer region in the years to come.